Tony Rice, a profoundly influential bluegrass guitarist and singer who united the canonical Southeastern tradition with West Coast experimentation, died at his home in Reidsville, NC on Christmas day at 69 years old. With a mellifluous baritone voice that thrilled hard core fans and curious newcomers in equal measure, Rice became perhaps the genre’s biggest solo star of the 80s and 90s. While his dextrous guitar innovations are regarded as the acoustic analog of the dazzling electric fireworks of Jimi Hendrix.

Rice refined and fortified the flatpicking style pioneered by Doc Watson and Clarence White into a hyper-articulate web of runs, scales and chordal decorations that astonished fans for decades and inspired thousands of guitarists to study his style like scripture. As devoted to his jazz heroes including George Benson and Oscar Peterson as he was to the founders of bluegrass, Rice introduced fresh harmonic color and daring to a genre that was largely raw and rural when he joined the performing ranks in the early 1970s. And he composed numerous fusion-minded instrumentals, such as the iconic “Manzanita,” that were as tricky as they were beguiling.

The bluegrass community lauded Tony Rice as word of his passing spread on Saturday. Ricky Skaggs, a longtime musical partner, announced the death on behalf of the Rice family, saying on Facebook, “Not only was Tony a brilliant guitar player but he was also one of the most stylistic lead vocalists in Bluegrass music history. When I joined the group The New South in 1974, I knew I’d found a singing soul mate with Tony. Our voices blended like brothers.” Chris Thile, the celebrated mandolinist and founder of Nickel Creek and Punch Brothers tweeted: “No one has had a more profound impact on my musical world. His playing, singing, writing, and arranging broke the bluegrass mold and will eternally attest to the fact that music can take you anywhere, from anywhere.”

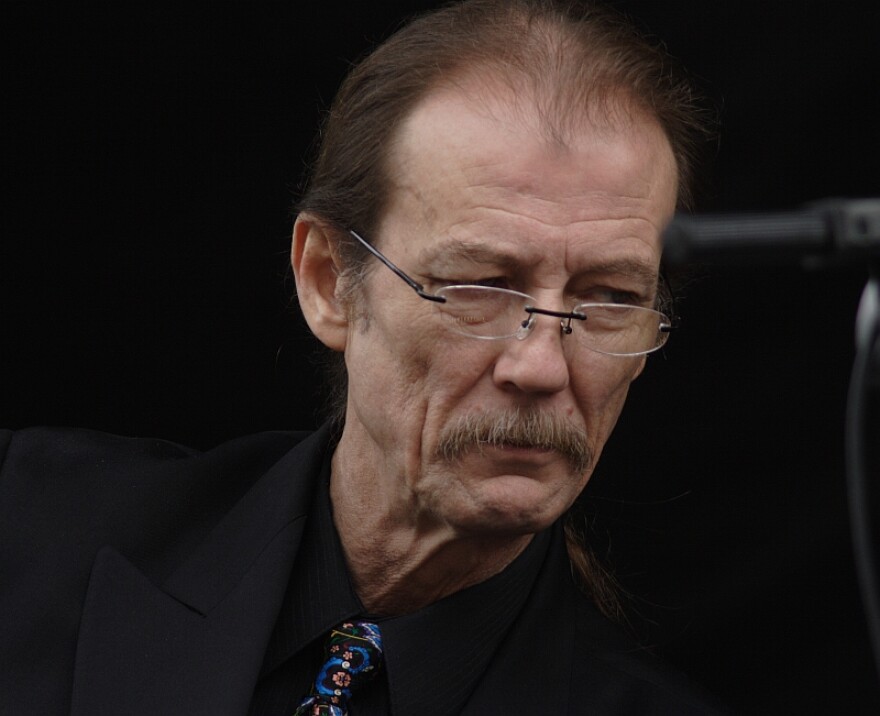

With his sometimes stony gaze and erect bearing on stage, a mystique grew around Tony Rice as he pursued ever-shifting collaborations, performances, clinics and all-star jams. He drove a Mustang SVT Cobra and led his bands wearing clean-cut suits, silk ties and a gold bracelet. His 1935 Martin D-28, formerly owned by Clarence White and revered by other players as the Holy Grail of bluegrass guitars, an instrument he nearly lost in a savage 1993 flood in Florida, had rattlesnake rattles in its resonating chamber. And he was beloved by those who worked with him as a warm colleague who flashed devilish smiles of musical approval on stage and who often concluded personal encounters with an “I love you.”

Rice played in historically significant bands with Kentucky superstar Skaggs, banjo legend J.D. Crowe, mandolin mystic David Grisman, star bandleader Doyle Lawson and newgrass pioneers Sam Bush, Bela Fleck and Jerry Douglas. He rebooted a good deal of standard bluegrass repertoire while also drawing on new realms of songwriters, notably Gordon Lightfoot, the source of so many Tony Rice sides over many albums that they were anthologized into the 17-track Tony Rice Sings Gordon Lightfoot in 1996. He was a Grammy-winner and a six-time IBMA Guitar Player of the Year. In 2013, Rice was inducted into the Bluegrass Hall of Fame.

Yet in the last decade, Rice has been more out of sight than on stage. Years of flawed vocal technique and smoking led to a muscular condition that forced him to retire as a singer in the mid 1990s. Then he was beset by arthritis in his hands and a nerve problem in his elbow. His last formal release seems to have been 2007’s Quartet with singer/songwriter Peter Rowan. In more recent years, fans contributed to a fund for the artist when he was unable to tour. Rice told his biographers that he’d rather stay out of the spotlight if his playing didn’t measure up to his exacting standards, and fervent hopes among fans for a comeback were never realized.

Rice was born on June 8, 1951 in Danville, VA, but he grew up in Los Angeles, where his father and uncle performed as The Golden State Boys. In the small bluegrass community there, his family grew close to that of Clarence and Roland White, who founded the innovative Kentucky Colonels. Clarence, who’d later spend time as an electric virtuoso in The Byrds, proved a seminal influence on Tony, with a novel and intricate approach to bluegrass lead guitar that emphasized control of the right hand. Where the instrument had spent the 50s as a rhythm instrument blasting out big chords behind vocalists and fiddle solos, White and then Rice found ways to emulate the role of a piano or a horn in a jazz band, with close harmonies, cross-picking and hammer-ons and pull-offs, a way of noting with the fingers on the left or fretting hand. Rice would become famous among players and aficionados for his “tone, taste and timing.”

Like the Whites, Tony started a band with his brothers Larry and Ronnie, around the time his family migrated back East. At a North Carolina bluegrass festival in 1970, Rice’s career truly got started when he took over for Dan Crary, another early flatpicker he admired (for his unusual volume), in The Bluegrass Alliance, the band that would soon evolve into New Grass Revival. Rice then started a four-year stint with J.D. Crowe, a banjo player whom Rice revered and emulated as he polished his sense of timing and bandcraft. Their six-nights-a-week sets at a hotel lounge in Lexington, KY became a magnet for bluegrass lovers and have been enshrined in the Bluegrass Hall of Fame and Museum. When new member Ricky Skaggs joined, the group recorded the seminal, must-own Rounder Records album (famously known for its catalog number 0044), J.D. Crowe And The New South in 1975.

Then it was back to California, where Rice teamed up with mandolinist David Grisman, the iconoclastic New York folk revival veteran who cooked up a new fusion of jazz, gypsy, Latin and bluegrass he called Dawg music. As time went on, Rice dubbed his own hybrid sound as a composer and bandleader “spacegrass,” through influential recordings like Acoustics in 1978 and Manzanita in 1979. Yet he also pursued exquisitely rendered old time string band and bluegrass music, such as the beloved acoustic vocal duo album Skaggs and Rice and his two refined folk duo LPs with Georgia guitarist Norman Blake in 1987 and 1990.

The 1980s were highly prolific, as Rice joined the all-star, classic-sounding Bluegrass Album Band for six releases and pursued a string of solo albums that captured his skills as an arranger and song interpreter. Besides the many Gordon Lightfoot tracks, he cut beautiful takes on songs by Ian Tyson, Mickey Newbury and Mary Chapin Carpenter. Rice was also the go-to guitar man for the instrumental acoustic experiments of the 1980s and 90s by banjo master Bela Fleck, around whom galvanized an informal supergroup - with mandolinist Sam Bush, dobro player Jerry Douglas and fiddler Stuart Duncan - that seemed to pop up at every festival on the circuit from time to time.

On a festival date in 1994, Rice felt he’d lost control of his voice so badly that he withdrew from singing live. He was later diagnosed with muscle tension dysphonia, which he explained in his biography: “It’s not that mysterious,” he told his interviewer. “If you use (your voice) incorrectly, it will wear out.” He cited singing too high with clenched muscles for too many years as the cause. But he also said it wasn’t where his heart was. “I never liked to sing anyway, man,” he said. “I always saw it as a distraction from what I wanted to do best, which was play the guitar.”

And yet one of the last in-person memories that many in professional bluegrass will have of Rice was his Hall of Fame acceptance speech in 2013 at the IBMA Awards. With apparent mental focus, his pinched, gravelly tone vanished and he conjured his old familiar speaking voice for a few moments that left many in the audience astonished and in tears. And that’s the posture so many find themselves in with Tony Rice’s memory this holiday weekend - thinking of his wife Pam and daughter India, remembering the many gigs, wishing there’d been more, and listening to the masterful recordings, snapshots of a unique career that brought a lonesome, rustic style closer to the heart of the American mainstream.