Music historians don’t even try to assign a specific inception date for the blues, jazz or rock and roll. But country music loves its birthdays, and there are plausible, evidence-based stories to tell about some of its “Big Bang” moments, especially for one genre. On December 8, 1945, Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys played the Grand Ole Opry at the Ryman Auditorium with a new lineup and thus a new sound, making this week the 75th anniversary of bluegrass music.

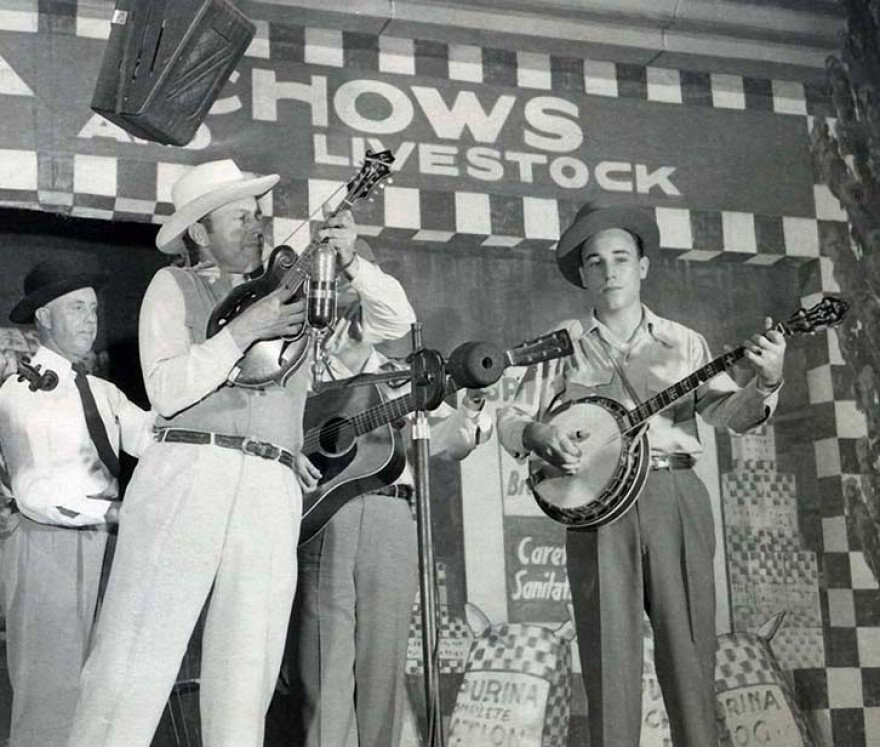

Monroe himself wasn’t the novelty that night. The strapping Kentucky-reared bandleader had been a top Opry star throughout the years of World War II. Besides being a mandolinist, songwriter and singer, Monroe was a band chemist, mixing sonic ingredients in search of a sound he claims to have had in his head. On 12.8.45, the new catalyst in the test tube was 21-year-old North Carolina banjo player Earl Scruggs. The self-taught musician’s specific mastery of the syncopated three-finger roll and his ability to play melodic solos at blistering tempos hit the Opry audience like a force field. A new synergy of string bass on the downbeats, Monroe’s mandolin on the off-beats (like the snare drum in an R&B band) and the Scruggs banjo sparked a groove as forward looking and propulsive as post War America itself.

Three quarters of a century later, bluegrass looks and sounds fantastic for its age, with a strong fan base, a talent pool that spans pre-teen prodigies to a few surviving navigators of the genre’s early days, and an ecosystem of festivals and commerce that defies the rules and confinements of the mainstream music business. There’s a lot to celebrate, and were this a normal year, events and moments would be taking place around the nation.

One that did go off nicely and appropriately was this Saturday night’s Grand Ole Opry commemoration, featuring performances by the venerable Del McCoury Band, their next generation side project the Travelin’ McCourys, new star couple Darin and Brooke Aldridge and recently crowned IBMA Entertainer of the Year Sister Sadie. In a pre-recorded segment, soon-to-be Opry member and multiple IBMA Award winner Rhonda Vincent told the Blue Grass Boys story and noted her thanks for a “life full of purpose, fire and passion.” She said “if it wasn’t for you, my dream to be an Opry member may not have been possible.”

By and large though, this diamond jubilee is yet another Covid bummer. Chris Joslin, executive director of the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Owensboro, KY, said Monday that he’s disappointed the whole affair can’t be a bigger collective deal. “We were working toward a specific night in December in our theater and distributing that as a livestream event with multiple artists, with storytelling and a lot of music to celebrate the 75th year,” he said. “That was our plan. But it wasn’t meant to be.”

That said, the Hall of Fame is the new owner and editorial caretaker of 54-year-old Bluegrass Unlimited magazine, and the so-called bible of bluegrass devotes its new December issue cover to the commemoration. Editor Dan Miller writes about the years leading up to and just after Bill Monroe’s 12.8.45 rollout and that band’s specific innovations - the demanding precision at fast tempos and three-part harmonies, the choreography around a single microphone, the jazz-like turn-taking of instrumental solos and the gospel quartet singing that became woven into the genre’s fabric.

The bluegrass origin story and the basics of what the music is has been well and widely told through books, documentaries and websites. But the 75 year mark got me thinking about the epic in three acts of 25 years each. It’s rough, but it works. Between 1945 and 1970, musician devotees of Bill Monroe’s new thing built a “first generation” of foundational artists, including Flatt & Scruggs, the Stanley Brothers, Reno & Smiley and Jim & Jesse and Jimmy Martin. They all pursued variations on a theme, establishing the remarkable balance between parameters and personal expression that’s kept bluegrass a coherent and growing genre. Act 1 also saw the birth of bluegrass festivals and the folkloric interest in the music that would solidify its name.

Youthful counter-cultural musicians had started to make waves in the conservative bluegrass world in the late 60s, but Act II between 1970 and 1995 was when musicians raised on and inspired by the pop culture crossover soundtracks of the Beverly Hillbillies and Bonnie & Clyde came into their own. New Grass Revival launched in 1972 and played arenas with rock star Leon Russell. The bluegrass-infused multi-generational triple album Will The Circle Be Unbroken dropped that same year, inspiring new audiences and musicians like nothing before it. Super pickers like Sam Bush, Bela Fleck, Jerry Douglas and Tony Rice became stars with approaches that borrowed explicitly from jazz, rock and roll, Celtic and beyond. The International Bluegrass Music Association was formed, along with its industry-standard awards.

By 1995, bluegrass was due for a renewal, and it came in large part from veteran country music stars seeking that archetypal return to roots. Ricky Skaggs retired his country act and launched his ultra-successful bluegrass band Kentucky Thunder in ‘97. Dolly Parton made her magnificent The Grass Is Blue album. From within the bluegrass family, Del McCoury achieved a kind of traditionalist patriarchal status after the death of Bill Monroe in 1996. And the release of the bluegrass-adjacent soundtrack to the film O Brother, Where Art Thou? (whose 20th anniversary was last week) became the 21st century calling card for acoustic roots music, and the sector has been robust and fertile with talent ever since.

No surprise, the 12.8.45 theory is the subject of debate. Monroe himself considered 1939 the birth year of bluegrass. Monroe’s December ‘45 band made two more personnel changes by early 1946 to create the legendary “fab five” (Monroe, Scruggs, Lester Flatt, Chubby Wise, Cedrick Rainwater) who would galvanize and spread the new bluegrass sound over the next couple of years. But that’s the thing about history. It didn’t unfold so that we could have neat and tidy birthday celebrations. Suffice it to say that if you pop on some Bill Monroe records this week, as you should, there’s no bad time.