Journalist Marissa Moss spent her post college years working in political communications and progressive causes, so when her real dream of music writing got up and rolling, combining the ethos of those two worlds came naturally. “I was always interested in that intersection of music and social justice,” she says. “Sometimes people will yell at me on Twitter or write an email after an article and be like, you're clearly politically motivated. Surprise! It's always kind of been who I am.”

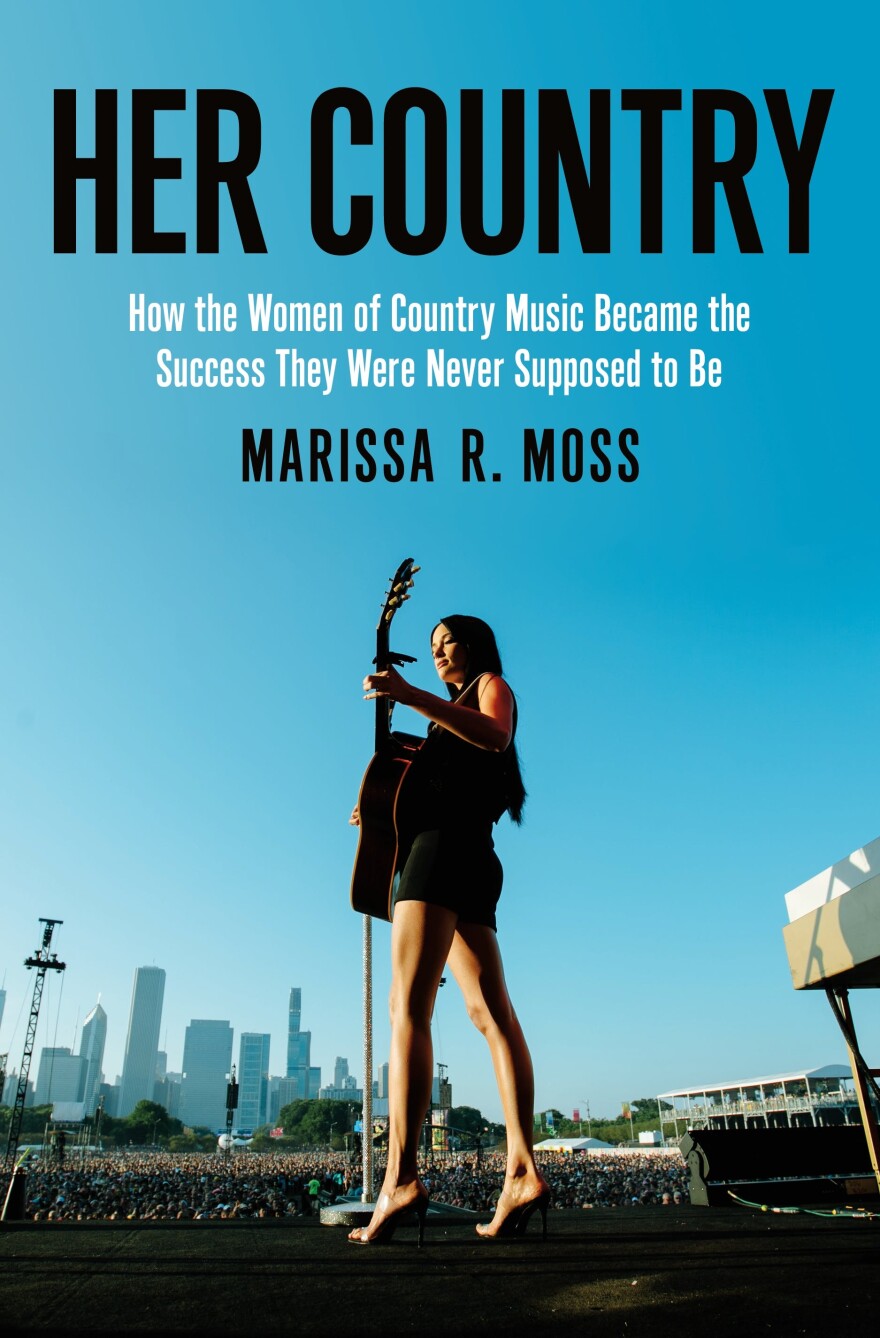

In a time when the country and its culture are being scrutinized and analyzed more than ever for injustice and inequity, Moss has been in the vanguard of journalists investigating the art and business of country and roots music. Her articles for Rolling Stone, the Nashville Scene, and American Songwriter have often foregrounded the specific struggles of women, people of color and LGBTQ artists in the 21st century music business. Particularly noteworthy was her 2018 exposé in Rolling Stone about sexism and sexual harassment faced by women in the country radio ecosystem. Now she’s followed that with her first book, Her Country, How the Women of Country Music Became the Success They Were Never Supposed to Be, which chronicles recent history in the genre through the interwoven journeys of Kacey Musgraves, Mickey Guyton and Maren Morris. The obstacles they confront on the way from their home towns to Nashville and musical success are a mix of the normal difficulties of trying to be chosen from the mass of aspiring artists to direct and indirect sexism and racism.

Nobody’s described this recent era of country music in book form yet, so Her Country will be a key document of its time. And Moss’s experience as a journalist asking harder-than-usual questions of Music Row reveals a lot about the insular and change-resistant culture of the industry. I enjoyed sitting down with Moss to talk about it. The text conversation has been edited for space and clarity. You can hear our full talk via the audio.

When did you get passionate about country music in the first place?

I grew up in New York City, not a place where people immediately associate with country fans, I guess. But I had a dad who loved 90s and 80s country. He would play country radio, and I would make fun of him at the time. Of course, now he has the last laugh, because here I am. But I got really into the Grateful Dead and Bob Dylan and really wanted to understand who influenced them. And that's what led me to the beginnings of my country wormhole. My brother plays in old time and bluegrass bands. He bought me a bunch of early fingerpicking records and I got really excited by those. All my friends thought it was so strange.

Then as a reporter, you sought out stories that went beyond mere profiles of artists and albums an into issues.

I remember when I came here about 11 years ago, I was kind of a weirdo. Because I really loved what was going on in Americana and the East Nashville scene. But I also liked a lot of what was coming out of mainstream Music Row. And sometimes it felt like you had to pick a side, and I didn't really want to pick a side. But then when I would go hang out in a Music Row context, I felt so angry and like an outsider all the time. Like, no one was asking hard questions at these weirdo (artist) round tables. I got, you know, banned from covering the CMA Awards because I wrote something too sarcastic about being in the press room. I obviously knew what happened to the (Dixie) Chicks, so that it feels like there was this smaller scale effort to apply ‘shut up and sing’ to journalists too. Just be here and play nice and don't say anything mean, and don't say anything critical. And, you know, that's just not how it works like, we're a family. Everybody says nice things all the time. But there are so many injustices happening and inequities in so many areas, how can you do that? Like, how do you exist in that space?

Tell me about the thought process that led Kacey Musgraves, Maren Morris and Mickey Guyton – all from Texas - to be the protagonists of the story you wanted to tell.

I knew right away that it couldn't be an Americana story. It had to be artists that were squarely within the business of country artists on Music Row labels in the now, you know, not in the early 2000s or the late 90s. And I wanted to focus on a singular place and path for narrative ease. But I've always been really fascinated with artists from Texas, from Guy Clark to Kacey Musgraves. And spent a bunch of summers in Texas when my dad lived there, outside of Austin. So I have a connection to the place. And I wanted to bring in other artists like Miranda Lambert and The Chicks, like North Stars. So I landed on these three women that both really defined success on their own terms in three very different ways. I wanted to make the story intersectional, and I happen to really love and respect their music.

Mickey Guyton’s story is particularly troubling. She was signed to Capitol Records as if they believed in her around 2011 – the first black woman on a country major maybe ever, and then they went about a decade without giving her the budget and green light to make an album. What does the label head Mike Dungan say about why that was?

I mean, I haven't asked him. But yeah, Mickey came to Nashville around the same time as Kacey and Maren, and that was really another important reason I put all three together, because they all came here around the same time and had the same next level talent. Mickey is kind of the most country of all three, in terms of country radio, you know? There’s not one person to point a finger at. It's really a broken system. And I think what someone would say at the label, I don't know, but I would imagine that they would say, you know, it's this system where, you know, we tried to put out this song, and it wasn't getting put into rotation, or put it back on the listeners. Radio programmers put it back on the label for not shipping the song timely enough. There are so many broken pieces, like a system that is essentially built to fail someone like Mickey. I remember she came out with her first single in 2014. She debuted it at the Ryman Auditorium. I assumed very naively that she would be successful, because everything was kind of there. It felt in the Carrie Underwood lane to me. I just sort of assumed it will work and very quickly learned and educated myself that no, that’s not going to happen.

Her story certainly seems like the hardest road of the three.

Yeah, I do not know how she did it. And I'm saying this as a white woman too. So I can't even imagine one little iota of what her struggle actually felt like, but I wouldn't have stuck it out. People will come at Mickey on social media and get mad at her and be like, you must hate country music. You know, like, is there anyone in town that loves country music more than Mickey Guyton right now? Probably not. Because why on earth would you stick around for 10 years of getting every door slammed on you? I can't imagine after 10 years, you know, they still don't put out your album. You have all these great songs, and they're saying they're not right. You're seeing Joe Schmo mediocre dude in a trucker hat get number one songs and you know you're still not making a record - like that's gonna kill you. The fact that you can stick around through that is what is just nuts to me.

Once nicer story you tell that involves all your characters at one point or another is the house dubbed Hotel Villa. What was that and how did it support artists?

Yeah. Ever since I heard about this place, I think probably first from Charlie Worsham, I was fascinated by it and maybe have romanticized it a little bit. But there was a house that a bunch of artists rented on Villa Place up in Edgehill. And they called it Hotel Villa. Now since then, I think it was torn down and turned into like a $3 million stately home or something. You know, Nashville. But at the time it was kind of a wreck. And Charlie Worsham lived there. And Brothers Osbourne and all these different musicians came in and out and just hung out and jammed. Kacey came through there. Ashley Monroe, Kree Harrison, Mickey. It was a little bit of a Chelsea Hotel vibe, where just musicians came in and built this community and no one had any money and no one really had record deals yet. I wish I could have been in been a fly on the wall at the hotel villa. But I was really enchanted by those stories.

You call up the story of the then-Dixie Chicks, who were basically banished from country radio overnight when singer Natalie Maines criticized President Bush’s war policy on a stage in the UK. I covered that at the time, and it was crazy. And it was a death knell for women on country radio, because there were many on the charts before that. After 2003, not so much. That’s where suddenly the shut up and sing thing became very real.

Yeah, I mean I was living in New York at the time, not too far from where the World Trade Center was. So that was my perspective, and I remember the Chicks had this whole feud with Toby Keith and I remember how that felt. I think that something would have happened to mute their voices if it wasn't that one incident. I do. I don't know if I want to say that there was relief when that happened. But people were so eager to find an excuse to silence outspoken female country musicians that you have to believe that maybe some of that sentiment existed before that. It was like the last drop of water in the cup about to overflow, and not just one isolated thing.

Radio really made that call – a few powerful corporate programmers. But at Nashville’s labels, there’s no shortage of liberal, progressive and gay people in the business. Did you get a sense that the labels generally feel powerless or frustrated about their ability to kind of widen the aperture for the music, bring in more diverse voices?

Yeah, I know there are a lot of people out there that probably feel that way. And I understand it, to a certain degree. It's also very frustrating to write an investigative piece, or even this book, or I'll tweet something, and I'll get a bunch of texts from folks in the industry being like, thank you for saying that, you know, somebody had to. But that's private, you know? They're texting me privately to say that. And they’re kind of like, we're on the good side with y'all. And that doesn't make me feel any better. That kind of makes me feel worse, because it's like, okay, so you agree with me that these things are broken, or that there's these deep inequities, or the shift away from a certain style of music, all of these things. But you don't want to do anything about it with your position of power. And that's really frustrating. You can't make change until people start making change.

You wrote a powerful piece for Rolling Stone about the radio tours and the sexual indignities and harassment that goes on there. You allude to that in your book, but you didn’t go as hard-hitting with background sourcing and quotes from inside radio. Did you want this to be a different kind of work of journalism than that Rolling Stone expose?

Yeah, and I thought about it a lot - the different ways that I could do this story and different stories I could tell. And what I wanted to do, and what was important to me, was to tell women's stories kind of purely. Something that's lacking for me is like, whenever I'll see women in country written about, it incorporates the, the struggle, always, especially with Mickey. It's always part of their narrative. And we focus on the hardship and them speaking out about Me Too, or politics or all these things. And what I was really missing was their purely organic stories, growing up loving music shaping how they became musicians - stories that I know and I've read many times of so many male musicians. And so that was when I was kind of figuring out how to use my space, I wanted to devote more to those stories than what I went into in that article. And I wanted it to be something that was accessible enough in a way for a lot of different people. Because like I said, I like I really do love country music of all kinds. And that was one other thing that I really wanted to do with the book was, you know, show the deep kind of systemic failure but more than anything, make people fall in love with these women and with country music, if they hadn't before. If they felt like they had been left behind by it - if they felt like, oh, I like anything but country music, kind of musical snobs, that maybe they would reconsider that. So that was my focus.

The book does end with some wins and triumphs, like Kasey winning major awards for “Follow Your Arrow” and an Album of the Year Grammy. She's touring arenas. Maren Morris is a genuine hit country singer, who seems to be able to kind of create her own reality. Mickey’s blessings are more mixed. It suggests that country radio isn't really changing, but the rest of the music business has changed. So where does this leave us?

It was a hard book to end, because the story is so in motion, you know? I didn't want to leave too optimistic because that didn't feel accurate, and I didn't want to feel too pessimistic because that's not useful, and not the whole picture either. In this process of talking about the book, people have asked me who are you excited about? And every time I can say different people. I can list off like 20 different people. There are so many artists and music makers that I'm excited about right now. There's so many people doing really exciting work on all different parts of the spectrum from you know, the Black Opry advocating for and creating a space for black artists in country and Americana. You know what's going on in AmericanaFest this year. And last year in the work that they're doing. To people doing interesting work over on Music Row making music that pushes the boundaries in the mainstream country space. So I'll have my days where I am very angry and depressed and frustrated when certain things happen. But what centers me back and makes me put one foot in front of the other is the music, and that I don't feel like we are lacking.